.jpg)

.jpg)

I, Alexander McLean, am privileged to have founded and to direct the Justice Defenders. We are a family of prisoners, ex-prisoners, prison officers, lawyers, judges and supporters. We are a bunch of broken and beautiful people working to put the power of the law into the hands of the poor. Death row inmates in Uganda have nicknamed me a prisoner by choice, forgetting that since the age of twenty-one I have been a magistrate in the UK and have sent people to prison myself. With Justice Defenders we are building a community of prisoners, prison officers, lawyers and supporters who are willing to go to the margins of society, to the places where others don’t want to go, seeking to bring justice, dignity and hope.

A Turning Point in My Life

I went to Uganda when I was eighteen years old, initially to spend a couple of weeks volunteering in a hospice hoping to share the love of Christ with the patients. My parents thought I was crazy and tried to bribe me not to go ahead with this project. To begin with, I shadowed the hospice doctors and nurses as they went on home visits. It was fascinating but, as a British teenager, there wasn’t anything very useful I could do. Occasionally, I would be asked to say a prayer for a patient.

The first man I cared for in hospital was lying on the floor by the toilet. I asked a nurse about his condition and she told me that he had been found unconscious by the police at a market. They didn’t know his name or whether he had any family, and suspected that he was in a diabetic coma. Because he had no money, he got no care. I saw that he was lying in a pool of urine with the flesh on his bottom and back rotten down to the bone. He was decomposing whilst still alive. I returned the next day, and with the help of a nurse trained by the hospice, washed him, got him bedding and tried to advocate for him with the doctors. For five days I washed and lobbied on his behalf. I came on the sixth day and discovered that he had died during the night. After a while a porter came with a trolley with a dead woman on it and put the man on top of the woman.

I understood they would go to the mass grave together with everyone else who had no one to bury them. I realized that there are people whose lives are judged to have no worth by their community or government. This left me 1furious and heartbroken, yet motivated to bring dignity to those deemed worthless. I called my mum that evening and cried for that man. It was a turning point in my life as I realised that there are people in our world whose lives are judged by their communities to have no value.

A Desire to Serve the Rejected

I ended up spending several months on a ward, washing, feeding and advocating for patients dying of HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis who had been abandoned by their families. Over time others began to join me – cooks and security guards from the hospice, student nurses and medical students, Ugandans and people from different parts of the world. We had little money, limited qualifications, no organisation but we had a desire to serve those whom others had rejected, inspired by Jesus’ instruction that we should love our neighbours as we love ourselves. It was then that I began to learn something about the power of proximity. Pope Benedict remarked that in serving others we need to have skills and something to offer, but even more important is the formation of our hearts. This enables us to see Christ in others and to share with them something of our very selves.

Many of the patients we looked after were prisoners, often teenagers imprisoned for underage sex, which in Uganda has a maximum penalty of death. Spurred on by this realisation, I succeeded, with dogged persistence, in gaining admittance into Uganda’s maximum-security prison. As I walked the hallways, I learned that two thirds of the prisoners hadn’t been tried. I visited death row, designed for fifty prisoners but now holding five hundred. There I heard of Edward Mpagi who had been sentenced to death for murder. After twelve years on death row, it turned out that the person he had supposedly killed was still alive. It would take another six years before he would be released. I was told of another prisoner who had stolen a mango from a neighbour’s tree using a Stanley knife. He had been sentenced to death for armed robbery.

Inmates could find themselves imprisoned for many years without trial and without access to a lawyer. We looked after Charles who was accused of theft. When the police arrested him they beat him until his skull was fractured in three places and he was bleeding out of his eyes and ears and bottom. We looked after Peter who had Aids, cancer, and Norwegian scabies which makes the skin peel off your whole body. I got scabies from him. I learnt that proximity changes us, that from a distance it can seem that certain people, such as prisoners, or people of a different faith, are very different from us. Up 2close, I saw that fundamentally each of us longs to feel seen, known and loved.

Eradicating the Roots of Injustice

I returned to the UK to study law at university and qualify as a barrister, while spending my university holidays in Uganda, Kenya and Sierra Leone establishing prison libraries and clinics. I went on to visit more than a hundred prisons all over Africa and saw remarkable similarities in the challenges faced by the legal system. I saw things that I couldn’t conveniently forget. Injustices clouded my senses in a place meant for justice. Change could not be postponed. In 2007, when I was twenty-one, I registered the African Prisons Project, now Justice Defenders, as a UK charity. Initially our work was to bring dignity and hope to men, women and children in prison through providing health and education facilities. Throughout our first few years we bathed dying prisoners, established prison clinics, and ran prison education programmes.

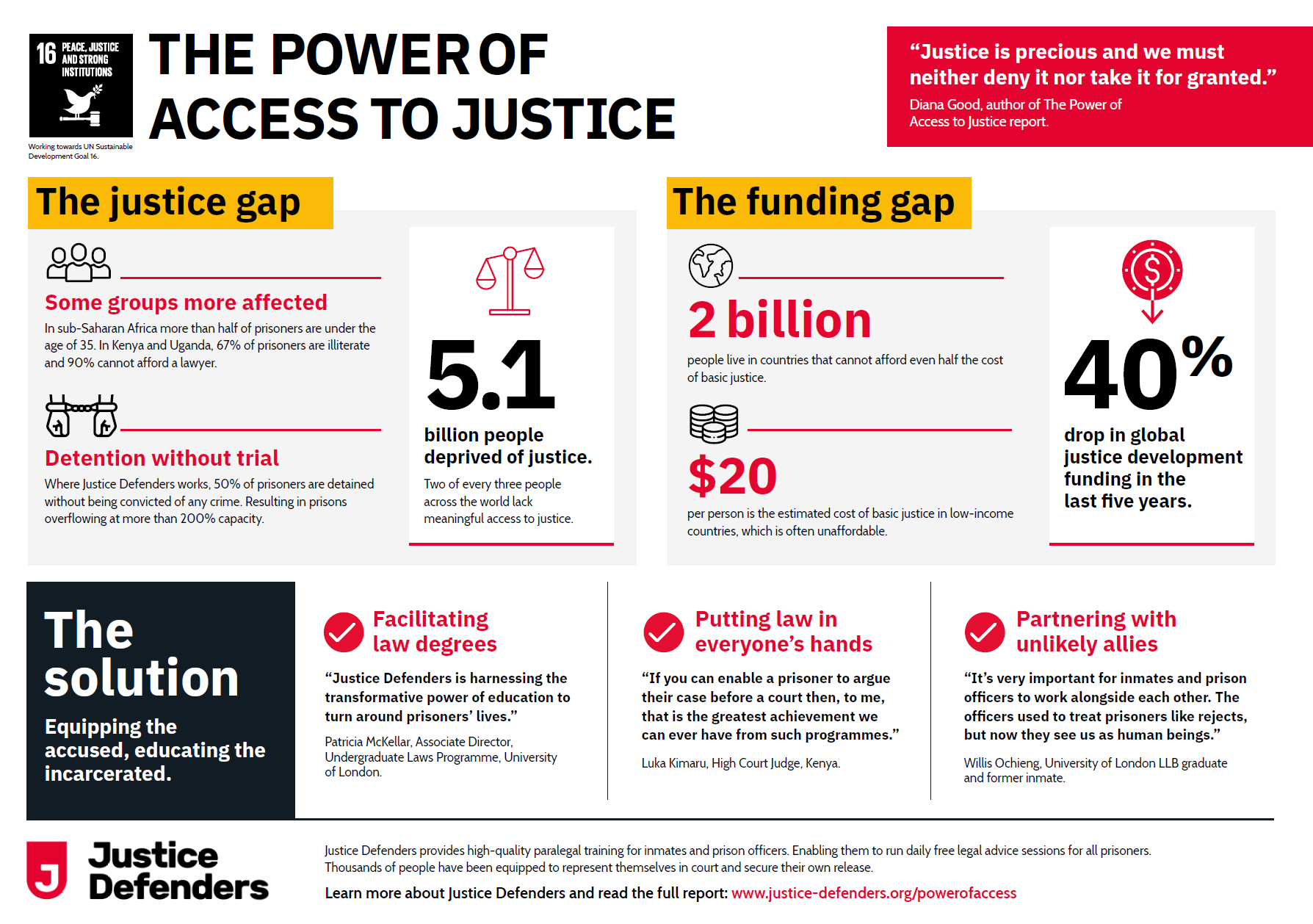

Over time, we began to question why almost all of the prisoners we met came from the poorest, most vulnerable parts of society; and why those who made and implemented the law came from backgrounds of greater privilege. Gradually, our focus shifted from dealing with the results of injustice to eradicating the roots. In countries where 80%-90 % of prisoners have no lawyers, we train prisoners and prison officers together as paralegals and lawyers. We work to equip those who have been defenceless to become defenders of the defenceless. We recognise, as St Oscar Romero said, that “certain things can only be seen with eyes that have cried.”

Our experience led us to the conclusion shared by Bryan Stevenson: “The opposite of poverty is not wealth. In too many places, the opposite of poverty is justice.” We made some shocking discoveries, not least among them being that up to half of prisoners are thought to be innocent. We saw that, without justice, simply improving the welfare of people in prison would provide no long term solution. As well, I came to understand that around Africa, in countries filled with well-meaning NGOs, very few are working in prisons.

And yet, in prison you find the most vulnerable people imaginable: children of five imprisoned alongside their mothers; those who have tried to take their lives imprisoned for attempted suicide; those who have had their fingernails pulled out or been raped by the police. People are sent to prisons which are standing room only. In some cases women give birth to babies who die on the floors of overcrowded cells and adults suffocate for lack of oxygen. I was told by a prison officer of a three-year-old child swimming in a river with a five-year-old friend. The three-year-old drowned and the five-year-old was sentenced to death for murder.

Making Bridges between the Rich and the Poor

In 2017 our focus shifted from making prisons better to providing access to justice. A few years later in 2020 we rebranded and relaunched as Justice Defenders. Our mission? - equip defenceless communities with legal training to defend themselves and others. Who better to be involved in making, shaping and implementing the law than those who have experienced conflict with it? Prisoners, ex-prisoners, and prison staff offer unique perspectives on legal systems. Yet their experiences are rarely acknowledged. Bringing them together with prosecutors, the police, judges, experienced lawyers, and academics creates remarkable possibilities for good.

So, who are we, really? We are justice-oriented individuals from different countries, faiths and social groups. All of us are guided by one statement: “We are a community of servants, accountable stewards and courageous changemakers.” I’m deeply inspired by the prisoners and prison officers we work with, but especially by the prisoners. They may be living in a cell which they share with eight other people. They may not have a bed, or a proper toilet. They may not get to see their children more than once a year. But if they are still able to be kind, to offer hospitality and to study, even when it has to be by torchlight, what does this mean for me in terms of the courage I might have, or the compassion I can offer to others?

Last year, having received paralegal services from our community, approximately three thousand people were released by the courts from prison in Uganda and Kenya. Our first graduate, Moses, has gone from being a prisoner to being a prosecutor in the Ugandan army. Our students, from within prison and on death row, have been involved in both Uganda and Kenya in Supreme Court cases which have resulted in the abolition of the mandatory death sentence. A judge no longer is obliged to give the death penalty. We believe that we can all play a role in making, shaping and implementing the law, because the law, from before we are born until after we die, affects us all. We long for the mystique and pride which clouds so much of the legal system to evaporate, so that we can clearly see that the law is a tool to serve democracy and the safe functioning of our societies.

A Revolution of the Heart

When we see injustice and inequality, of which there is an abundance here in the UK, as well as around the world, we can and should become angry. What will we do with that anger? Often it can burn out or become apathy. What does it look like for us to overcome anger and apathy and to act? As we work in adversarial justice systems, I believe that we have the opportunity to make bridges of our lives – between the rich and the poor, those with power and those without it, between black and white. And I believe that there’s a joy which comes with being close to others working for justice.

We delight in finding common cause. We are proud of our prison officers who go to court on behalf of prisoners in order to win their freedom. We work hand in hand with the judiciary and are pleased to bring them into the prisons to share meals with our paralegals so that they can discuss together the challenges facing the community. As we study and practise law together, we hope to grow in love for each other and those we serve.

We are proud to showcase radical aspiration and black excellence. Last year we had five students achieve 1st class marks, the highest the university awards. In 2018 we saw an average of two hundred and fifty people each month released from prison having accessed legal support from our paralegals. We are now asking ourselves what it would look like to establish a law school to train our most vulnerable people in law - prisoners, refugees, the homeless and prostitutes; and how we could establish a law firm which would provide high quality, low cost legal services to those who wouldn’t otherwise be able to access them.

It’s now almost twenty-two years since I started volunteering in my church and local hospice and twenty since my first visit to prison. In that time we have raised more than £15 million to improve the lives of prisoners. We have trained six hundred paralegals; and we have sixty prisoners and prison officers in Uganda and Kenya who, following in the footsteps of Nelson Mandela, have studied law while in prison and succeeded in gaining degrees from the University of London. We have served more than one hundred thousand clients in our thirty-two prison based legal offices in Uganda and Kenya, of whom about thirty-five thousand have gone on to be released from prison by the courts.

And in all of this striving for justice and equity, the values of compassion and love must be at the core of everything that we do, 5remembering those wise words of the American social activist Dorothy Day: “The greatest challenge of the day is – how to bring about a revolution of the heart, a revolution that has to start with each one of us.”

Alexander McLean

.jpg)